Budget Chinese Airlines: You Get What You Pay For

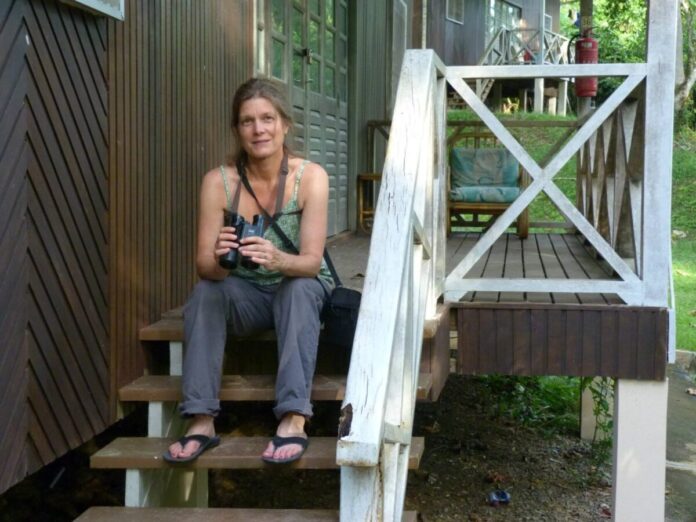

by Suzanne Tomassi

Every year I go to Borneo to do research for the University of Sheffield. I suppose I could write something about that spectacular experience, but I want to share some important advice first. Several budget Chinese airlines cost hundreds of dollars less than the really nice SE Asian lines, like Singapore Air and Asiana. I’ve always been curious as to why.

This year I found out.

The Lure of the Budget Chinese Airline

Lured by the price difference, I purchased what seemed like a fabulous flight. It took me from Seattle to Shanghai to Kota Kinabalu, with a 6-hour layover to allow for time to check out Shanghai, all for a good price. In the past, I have left pretty much everything I need at the field center, so I felt totally ahead of the game with only one bag of gear and gifts, my passport, and my international SIM card in tow.

A brief non-sequitur: I had terrible laryngitis and couldn’t squeeze out more than a raspy whisper. Seriously, I sounded like static. My husband even hung up on me because he couldn’t hear anything on the other end of the phone. This colors the whole experience.

My Journey Begins

I had crammed all my stuff into one bag instead of two, and as a result, my baggage was over the max weight. The airline was going to charge me $100 when a baggage handler overheard this and found me a cardboard box to transfer some of my items to (I could have up to 100lbs, but it had to be in separate bags). Voila! He’s saved me $100.

“I’m off to a good start!” I thought.

I was slightly unnerved when I found out the airline would only issue a ticket as far as Shanghai. They said I would have to go through immigration in China, pick up my bag, and check in again. But because I couldn’t talk, I didn’t ask questions. Besides, how bad could it be?

I expected a packed flight, so I wasn’t surprised when that’s what I got. What I didn’t expect, was to be launched straight into tropical weather at 36,000 feet. My window heated up until it burned my arm, which kind of made me wonder if I should have ‘fessed up about the extra lithium laptop battery I had in my checked luggage, but it mostly just annoyed me by exacerbating the already sauna-like conditions.

To my other side, a man struggling to take off his shoes repeatedly jabbed me in the ribs. A struggle that, in hindsight, I would have done my best to thwart given the spectacular stench that emanated from below, once he’d succeeded.

Next came the food. (I should have taken a photo, but that would have meant accessing my carry-on, which was on the floor and consequently close to my neighbor’s feet.) I’d ordered the Jain meal, and after I had convinced several flight attendants that it was indeed mine, my algae-on-Elmer’s-glue was delivered. No one expects good food on an airplane, so I was unfazed and ate the salad my friend Douglas had packed for me.

Over the next 14 hours I couldn’t sleep for fear of singeing my hair on the window should I accidentally lean against it in my sleep (there were no window shades, just tint you could adjust, which was actually pretty cool). So, instead, I watched instructive food shorts. All in all, what you’d expect, up to this point.

Arrival in Shanghai

Photo: ehpien via flickr

“Cool,” I thought, “a new airport!” Most Asian airports are luxurious, with free city tours for people with long layovers. They often include art exhibits, cultural performances, koi ponds, butterfly gardens, sleeping lounges, and lovely tiled showers. This one looked exactly like LAX, which is my now-second-least-favorite airport.

This is where it gets interesting.

I set off in search of my luggage, but am stopped at a kiosk and electronically finger-printed. I’m issued a card stating that my fingerprints have been obtained, and I’m sent to a line of immigration counters. No one seems to know which counter to go to, and I try several before arriving at one where I’m not told to leave. I am then told that the immigration form given to me on the plane is the wrong one, and I need to backtrack to find a blue one.

Whilst doing so, I’m passed by a group of foreign travelers who have just disembarked another plane. We will meet again, as they, too, will be passed from counter to counter and told to return with a blue form. In fact, we are about to experience something like Stockholm Syndrome together.

A German couple at a table covered with half-filled-out forms gives me a rumpled blue form and tells me it’s the last one. I make my way back to the counter for transit passengers, and now find a variety of foreign travelers milling about, forming lines that dissolve and converge on the seemingly-random instructions of immigration officials. Japanese nationals, for some reason, seem to have their own process altogether and are sent through a door not to be seen again. (I hope they are okay.)

When I reach an official, I’m told I must show proof of my ongoing flight, which I don’t have, because I wasn’t issued a ticket in Seattle. Nor can I show an e-ticket, because my phone won’t work in China (nor 50 feet underground, where I think this room happened to be). And, anyway, isn’t the whole point of an E-ticket that you don’t need a paper one? Now I’m faced with explaining my situation to the official.

Keep in mind that the only sound I can make is a short, high-pitched squeak, like air being forced out of a balloon, so I’m writing on scraps of paper and holding them up to the glass for the official to read. (Note also that my handwriting sucks under the best of conditions, which these were decidedly not. And, English wasn’t the poor guy’s first language.)

The official conveys to me that, while I might very well have an ongoing flight, I don’t have a Chinese visa, so I can’t go any further. I try to tell him that, if I’m going to live out the rest of my years in a Shanghai airport immigration waiting room, I would like to get my toothbrush out of my checked bag. He tells me to “wait over there,” and gestures vaguely to a yellow line. Then, he stops making eye contact with me.

I stand around and try to see whether other people have their proof of departure. Some of the ones that do, seem to make some progress, but a group of four men is held back because they cannot give the second room number of the cruise boat they have booked. Another group, a family, has their papers but is detained because they do have visas. Apparently, this is suspicious, as all other passengers obviously lack the visas that the officials are demanding.

Some people are sent to other lines, from which about half are sent back, or told like me to “wait over there,” after which they join me behind my yellow line. The luckiest make it as far as getting electronically fingerprinted again, despite showing their paper stating they’ve already been fingerprinted. This provides some entertainment for those of us still waiting; the machine has to record four sets of fingerprints and keeps repeating a word salad of: “place your left four fingers thumbprint for screen,” followed by “fail.”

The first successful people through are a couple of Spanish women, one of whom turns to smile sympathetically and tell me “Don’t give up,” as if that were an option. The group of hostages grows, and we attempt various group rebellions, but to no avail. The officials officially do not give a crap. We are chased back behind our yellow line.

From Bad to Worse

By now, an English couple and an Australian man have missed their flights. My six-hour layover has dwindled to three, with no end in sight. At this point, I have made my way to every official separately, hoping for a different outcome, and have been sent away each time. I was waved over to a lonely, ancient computer at one point, and I thought I might be able to get online and find my itinerary. But all I could get was what I figured were error messages in Chinese characters.

I consider crying, which would be easy, but then I remember that I’m old and no one cares if I cry anymore.

As the hostage situation heats up, a large group with a tour guide gets through and our hopes rise. But right then, the room empties of officials altogether, and we are left alone in this cinder-block-walled dungeon.

A new group of officials arrives shortly after and hopes rise again, but they avoid making eye contact with any of us. Not a good sign. Another hour ticks away. I see one with a phone and summon up the nerve to cross the yellow line, squeaking at him and waving scribbles explaining that he can look up my departing flight on his phone. In what I consider an enormous step toward resolution, he takes my passport and disappears. Bolstered, my fellow hostages begin negotiations with other officials.

Another hour passes.

With one hour to go until my connection, “my” official returns with my passport and my itinerary on his phone, and lets me take a photo of it. I’m then sent back behind the yellow line with the rest of the hostages, and we arrange ourselves into a line organized by the time we have to make connecting flights (I must say, we hostages really worked well together). I’m sent to the window, armed with my photo, and after about 10 minutes of staring at the photo on my phone and frowning disapprovingly at me, the official re-fingerprints and releases me!

Resolution

I turn to my friends still imprisoned behind the yellow line. “Godspeed!” I tell them through my tears and go in search of my luggage.

When I finally make it to the carousels, not surprisingly, my bag and box are not to be found. Jogging around the room frantically, I spot them on a cart with some other bags. Now I have to find the check-in counter for my flight. I don’t know the carrier, but I have the carrier code: FM. This stands for Shanghai Air, but I don’t know that yet.

“FM” does not appear on any Departures sign or check-in desk. I scour three floors looking for a hint. You can’t take carts between floors, of course, so I’m trying to lug my carry-on, my duffle, and a cardboard box full of books, up and down the stairs.

At the information desk on Floor 3, I’m told to go to Floor 1, exit the building, and cross the street to Terminal 1. On Floor 1, the exit door opens to a highway, with no other terminal in sight. No one in an airport uniform seems to know what Terminal 1 is or, more importantly, how to get there. Sounds like LAX, right?

I go back up the stair with all of my bags, to the information desk, and really want to demand to know why I was sent to a terminal that doesn’t exist but can’t make the words intelligible. This time I’m told to go to floor two and go outside to Terminal 1. “If I go outside on floor 2, won’t I plummet to my death on the pavement below?” I squeak. She doesn’t answer.

Perhaps she didn’t hear me.

With 20 minutes to go, I decide to try Floor 2. I figure, if I don’t find the right terminal at this point, I might as well leap off the second story anyway. But, lo and behold, when I step into the abyss outside the door of floor 2 there’s actually a catwalk across the highway! And, when I walk (run) across it, it takes me to terminal 1! This is where I discover that FM stands for Shanghai Airlines.

At check-in, I’m scolded for my tardiness but issued a boarding pass.

By comparison, the rest of the journey was uneventful. But, I’m definitely springing for Singapore Air next year!